Origins of Agriculture

The Origins of Agriculture: A Turning Point in Human Life

Agriculture began about 12,000 years ago, emerging independently in various parts of the world. The first crops and livestock were domesticated in six widely scattered regions, including the Near East, China, Southeast Asia, and Africa in the Old World, and Central America, South America, and Northeastern North America in the New World. This essay examines the origins of agriculture and the significant developments in this process.

Origins of Agriculture in the Old World

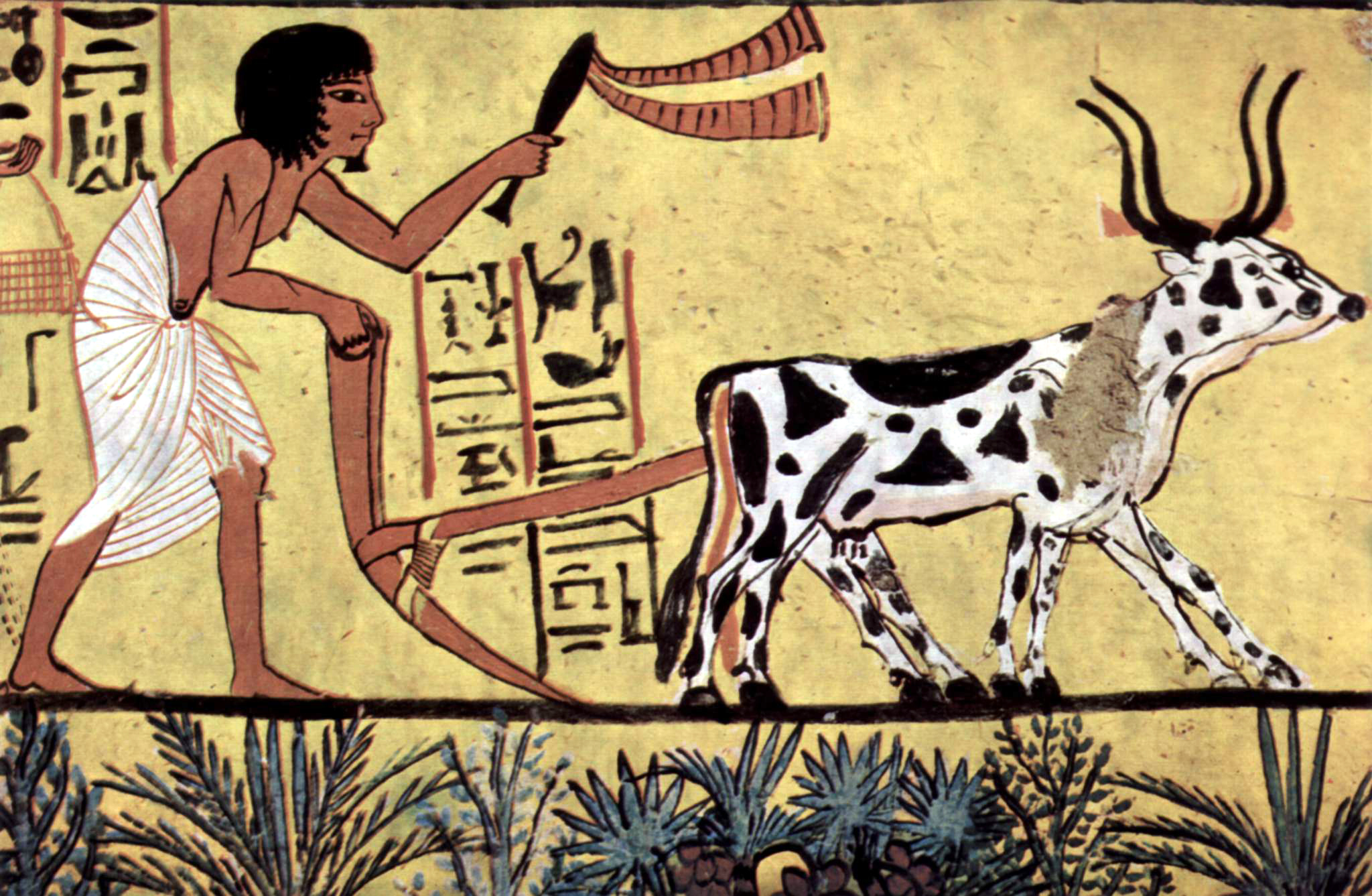

Agriculture began in the 4th millennium BCE in southeastern Turkey, western Iran, and the mountainous regions of the Levant. These regions had a wide variety of plants and animals suitable for domestication. Therefore, some scientists have suggested that the Near East should be considered a "nuclear zone," where events in one area influenced others.

HUMANS BEGAN DOMESTICATING PLANTS AROUND 12,000 YEARS AGO. The first farm animals, sheep, and goats were likely domesticated somewhere north and east of the center of plant domestication. Around 11,000 years ago, barley, wheat, goats, and sheep were domesticated in the Near East; followed by pigs and cattle 10,000 years ago, peas and lentils 8,000 years ago, and olives and grapes 6,000 years ago.

Agriculture also began very early in West Africa, Ethiopia, and the forest margins of the Sahel, an ecological transition zone between the Sahara Desert and the savannah to the south. Ethiopia provides the earliest evidence of African farming, dating back about 6,000 years, although other origins are likely just as old. Ethiopians domesticated coffee, millet, and teff. People in the Sahel domesticated sorghum, pearl millet, African rice, and guinea fowl. West Africans were responsible for domesticating African yams, cowpeas, watermelon, and palm trees.

China and Asia were also among the first regions of plant domestication in the Old World. There is evidence that cultivation was practiced in Thailand and New Guinea between 8,000 and 10,000 years ago. Two regions in China began farming about 8,000 years ago: the Yellow and Wei River basins in the north and the Yangtze Valley in the south. Bananas, taro, citrus, and sugarcane were first domesticated in Southeast Asia; broomcorn millet, foxtail millet, rice, soybeans, and pigs were among the first Chinese domestications, and chickens were domesticated in a region encompassing northern India below the Himalayas, southern China, and Southeast Asia.

Intercontinental Distribution of Near Eastern Plants

The Near Eastern grain culture spread rapidly, reaching Greece, Egypt, along the Caspian Sea, and Pakistan 8,000 years ago. Less than 1,000 years later, intensive agriculture was practiced in Central Europe, and 5,000 years ago, farming communities extended from the Spanish coast to England and Scandinavia.

Most of the founder crops of the Near East (einkorn wheat, emmer wheat, barley, lentils, peas, and flax) traveled to Europe in groups, encouraging the domestication of other crops along the way. Oats and flax began as weeds transported with the Near Eastern complex but eventually became secondary crops by the time they reached the Iberian Peninsula. Most vegetables domesticated 5,000 years ago, such as cabbage, onions, and radishes, also appeared as secondary crops.

The spread of agriculture to the Middle East and Europe might have occurred through cultural diffusion, where new techniques were passed from person to person through simple learning, or through migration, where transfer was associated with population growth and interbreeding. Much of the evidence supports the migration hypothesis, where the original lineage of agricultural peoples in the Near East gradually thinned as their descendants moved westward and interbred with local populations along the way.

Spread of Agriculture in the Mediterranean Basin

The spread of agriculture occurred on both land masses and Mediterranean islands. Recent evidence shows that the spread of domestications and agricultural economies across the Mediterranean was achieved by several waves of maritime colonists establishing coastal farming enclaves around the Mediterranean Basin. Cyprus was colonized around 10,500 to 9,000 years ago by fully settled Neolithic pioneers from the mainland. These colonists, probably traveling by boat, brought with them the full array of economically important mainland plants and animals, including sheep, goats, cattle, and pigs. There is also evidence of domesticated einkorn wheat, barley, emmer wheat, and lentils, along with pistachios, flax, and figs.

This model of colonization was repeated throughout the rest of the Mediterranean Basin. From the Aegean, there is strong evidence that seafaring colonists, carrying the full Neolithic package of crops, arrived around 9,000 to 8,000 years ago. The first maritime pioneers established farming communities along the Greek coast. Neolithic lifeways were introduced to the Italian peninsula around 8,000 years ago by seafaring colonists who first established agricultural villages in the "heel" of Apulia. In southern France, there is evidence of a colony of immigrant farmers from the Italian mainland, settled around 7,700 to 7,600 years ago.

Indian Ocean Dispersals

Indian Ocean seafarers sent a suite of important Asian crops, including sugarcane, citrus, Asian rice, Asian yams, taro, bananas, coconut, mango, breadfruit, and possibly several spices (ginger, cloves, and cardamom), to Madagascar, East Africa, and India in the 2nd millennium BCE. Many of these crops were later transferred across the continent to West Africa, including figs, sugarcane, citrus, cucumber, bananas, and African rice.

By the end of the 3rd millennium BCE, an India-Gulf trade network emerged between the coastal peoples of southern Arabia and the seafarers of Gujarat, India. Shortly thereafter, five African crops were transferred to South Asia: pearl millet, sorghum, cowpeas, and finger millet. This crop transfer likely took place in northeastern Africa and/or between Yemen and western India.

Moving in the opposite direction from India to Africa, Asian broomcorn millet (Panicum miliaceum), originally from China, began its westward journey around 2200 BCE. Zebu cattle were also likely transferred from India to Yemen and East Africa around the same time. Zebu cattle later hybridized with African cattle, producing hybrids that became significant for cattle herders in East Africa.

BANANAS FROM INDONESIA PROBABLY REACHED INDIA AND AFRICA AS EARLY AS 2000 BCE. About 5,000 years ago, many crops were domesticated in India, likely stimulated by the introduction of crops from Africa and Southeast Asia. These included eggplant, cucumbers, pigeon peas, mung beans, black pepper, ginger, sesame, cotton (G. arboretum and G. herbaceum), and rice (Oryza sativa ssp. Indica).

There is also evidence of regular trade between India and the Malay Peninsula by 1500 BCE. Mung beans (Vigna radiata) and horse gram (Macrotyloma uniflorum) were probably transferred from southern India to Southeast Asia around this time. Southeast Asian tree crops like the pomelo and mango might have been brought to southern India from the north, with likely origins ranging from the Assam/Burma/Yunnan region to the eastern Himalayan foothills.

Bananas from Indonesia, likely along with yams (Dioscorea alata) and taro, found their way to India and Africa as early as 2000 BCE. Bananas reached West Africa by 500 BCE, following the forested areas and the northern margins of the equatorial rainforests.

Chickens likely arrived in Africa from India via multiple routes. Historical linguistic data indicate three separate introductions: two from north of the Sahara and one from the Indian Ocean and the east coast of Africa.

Origins of Agriculture in the New World

Farming likely began independently in the New World, 1,000 to 2,000 years after the Old World. While there was a relatively compact Mesoamerican center stretching from present-day Mexico City to Honduras, South American crops emerged over a broad area encompassing coastal and midland South America. An independent center also emerged in the eastern United States.

Amaranth, avocado, beans, chenopods, cotton, chili peppers, squash, and gourds were domesticated in Mesoamerica, along with maize. In South America, domestication occurred in four general ecological/geographic zones:

- Central mid-altitude Andes (quinoa and amaranthus)

- Northern and central Andes, mid-altitude and high-altitude (potatoes, oca, and cañihua)

- Southern Amazonian lowlands (manioc and peanuts)

- Ecuador and northwest Peru (common beans and gourds)

Turkeys were domesticated in Mexico, while llamas and guinea pigs were domesticated in South America. North Americans were responsible for domesticating sunflowers, sumpweed, goosefoot, and possibly other gourd species.

Distribution of New World Plants

A maize-bean-squash complex gradually moved northward from the Mesoamerican center, incorporating sunflowers and many native species along the way, eventually reaching eastern North America about 4,500 years ago. Known as the "Three Sisters," this complex replaced native crops like sumpweed and chenopods. There is ongoing debate over whether these Mesoamerican crops spread to the Western Gulf Coastal Plain or moved westward to the southeastern United States.

Tracing the southward movement of most crops from Mesoamerica is challenging, but maize at least reached Central America and the Amazon basin by 5,000 to 4,000 years ago. South American domesticated crops like potatoes and peanuts traveled north to Mexico about 3,000 to 2,000 years ago, possibly traveling from Venezuela through the Caribbean islands or through Central America (or both).

Intercontinental Crop Exchanges – The Columbian Exchange

Until about 500 years ago, nearly all crop distributions occurred within continents, with little movement between hemispheres. When Christopher Columbus arrived in the New World in 1492 CE, farmers in the two hemispheres were growing entirely different crop complexes. The Americas also lacked large domesticated animals.

The complete homogenization of world crops did not begin until Columbus and other Spanish and Portuguese explorers brought back potatoes, chili peppers, and maize from Central America and tomatoes, beans, manioc, cacao, and peanuts from South America to Europe. European settlers attempted to transfer the entire European agricultural system to the New World. Spaniards introduced barley, chickpeas, cucumbers, figs, and wheat, initially domesticated in the Near East, as well as sugarcane and citrus from Southeast Asia, peaches from China, melons from Africa, and cabbage, lettuce, grapes, and onions from the Mediterranean. Portuguese settlers brought chickpeas, broad beans, figs, and wheat from the Near East, sugarcane and bananas from Southeast Asia, peaches from China, and other crops to Brazil.

Today, the world's people depend largely on crops domesticated far from their homes. Europe and North America rely on a mixed crop suite from around the globe, including wheat and barley from the Near East, maize from Central America, potatoes from South America, and soybeans from China. Africans have largely replaced their original sorghum, millet, and yams with maize from Central America, manioc and sweet potatoes from South America, and bananas from Southeast Asia. China’s original crops of rice and soybeans remain important but are now grown alongside maize from Central America and sweet potatoes and potatoes from South America. In the past 500 years, world agriculture has been turned upside down.

Global Impacts of Agriculture

The beginning of agriculture is one of the most significant turning points in human history. Agriculture enabled humans to transition to a settled lifestyle, form communities, and build civilizations. The evolution of agriculture is directly related to technological advancements, changes in social and economic structures, and the increase in human populations.

The spread and development of agriculture increased interactions between societies, opened trade routes, and led to cultural exchanges. Agriculture also intensified humans' impact on their natural environments, leading to deforestation, soil erosion, and loss of biodiversity. Despite these negative impacts, agriculture has played an indispensable role in humanity's survival and development.

In conclusion, the origins and evolution of agriculture are crucial for understanding human history. Agriculture has shaped how humans interact with their environment, their social and economic structures, and their cultural development. The current global impacts of agriculture result from this long and complex process. Through agriculture, humans have survived, grown, and developed, and this process will continue into the future.