The Consequences of the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution in England: A Transformative Era with Long-Lasting Effects

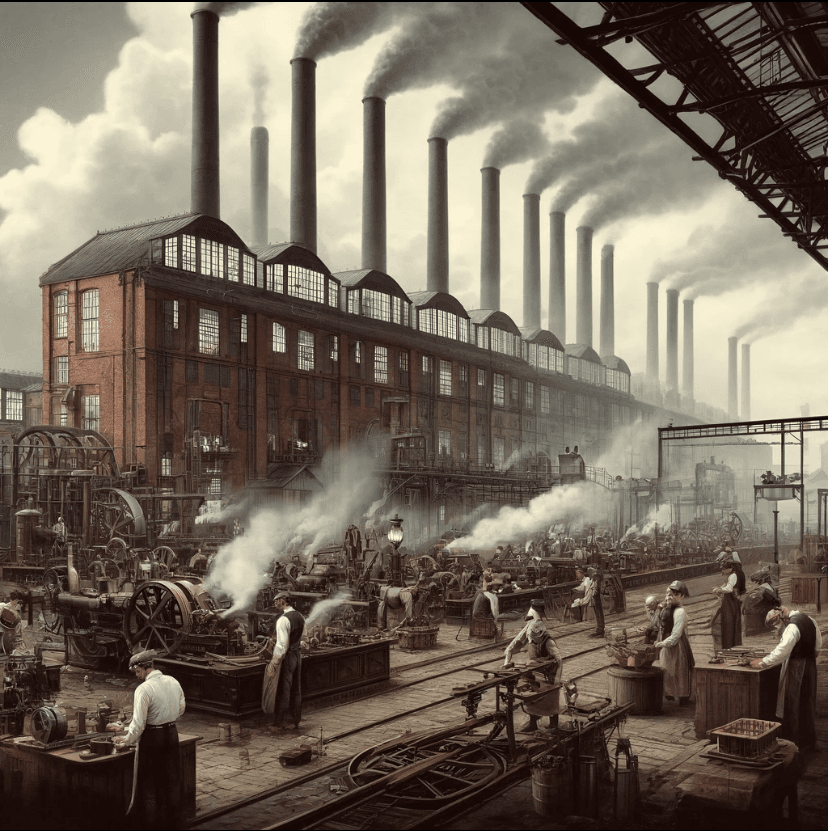

The Industrial Revolution in England (1760-1840) brought about profound and long-lasting changes in various fields. The invention of new machines, the proliferation of factories, and the permanent decline of traditional handicrafts led to significant shifts in the working lives of both rural and urban areas. Advances in transportation and communication further accelerated the pace of life in the post-industrial world, making human connections more critical than ever before. Consumption goods became more accessible to a broader segment of the population, and the purchasing power of individuals improved significantly. This period saw an explosion in urban population growth, creating more job opportunities in cities. However, the price for these advancements included overcrowded cities, poor air quality, increased crime, noise pollution, monotonous repetitive work, and dangerous working conditions.

The Impact of the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution's impact spanned several areas:

- Innovation and Mechanization:

- Numerous machines were invented that performed tasks faster than ever before or enabled entirely new types of work.

- The use of steam power provided a more cost-effective, safer, and quicker alternative to traditional power sources.

- Large factories were established, creating jobs and leading to a boom in cotton textile production.

- Engineering and Infrastructure:

- Major engineering projects, such as the construction of iron bridges and viaducts, became feasible.

- Traditional industries like handloom weaving and stagecoach transportation saw a significant decline.

- Mass production and reduced transportation costs lowered the prices of food and other consumer goods.

- The coal, iron, and steel industries experienced explosive growth, providing the fuel and raw materials needed to power machines.

- Urbanization and Labor:

- Urbanization accelerated as the workforce concentrated around factories in towns and cities.

- Rail travel became more affordable, and the demand for unskilled labor increased, particularly in textile factories.

- There was a significant rise in the employment of women and children.

- Worker safety deteriorated, and it wasn't until the 1830s that improvements began.

- Social Changes:

- Trade unions were established to protect workers' rights.

- The success of mechanization inspired other countries to undergo their own industrial revolutions.

The Rise of Coal Mining

England had a long history of tin and coal mining, but the Industrial Revolution significantly increased underground activity to supply fuel for steam-powered machines in industry and transportation. In 1712, the invention of the steam-powered pump helped drain water from mine shafts, allowing for deeper mining and a significant increase in coal production. James Watt's steam engine, patented in 1769, enabled the use of steam power across almost all sectors, leading to a mining boom.

By 1825, railways had spread across the country, and by the 1840s, steam-powered ships further advanced the progress. Coal gas began to be used for lighting homes and streets, heating private spaces, and in kitchens by 1812. Coke, a type of coal, became an essential fuel for the iron and steel industries, driving up coal demand as the Industrial Revolution took hold.

Textile Industry Transformation

The steam engine revolutionized British industry, particularly the textile sector, one of Britain's largest industries. Spinning and weaving activities, initially small-scale cottage industries, underwent a dramatic transformation with the invention of several revolutionary machines. Notable inventions included:

- Flying Shuttle (John Kay, 1733)

- Spinning Jenny (James Hargreaves, 1764)

- Water Frame (Richard Arkwright, 1769)

- Spinning Mule (Samuel Crompton, 1779)

- Power Loom (Edmund Cartwright, 1785)

- Cotton Gin (Eli Whitney, 1794)

- Roberts Loom and Self-Acting Mule (Richard Roberts, 1822-25)

These machines, initially powered by water and later by steam, outpaced manual machines in speed and cost-efficiency. By the 1830s, 75% of cotton-processing factories were steam-powered, and cotton woven goods accounted for half of England's total exports.

Despite the benefits of mechanization, there were significant protests, especially from textile workers. Between 1811 and 1816, the Luddites, led by the mythical figure Ned Ludd, famously destroyed factory machines. Factory owners responded harshly; damaging machinery was a crime punishable by death.

Agricultural Innovations

The industrialization process in Britain was marked by both decline and innovation in agriculture. On one hand, the sector faced a downturn; on the other hand, innovations and mechanization made farming more efficient, capable of feeding the growing population. In 1800, agriculture accounted for 35% of the British workforce. By 1841, even in the late stages of the Industrial Revolution, one in five Britons still worked on farms.

Mechanization helped offset Britain's relatively high labor costs and encouraged rural-to-urban migration. Notable agricultural inventions included:

- Rotherham Plough (Joseph Foljambe, 1730)

- Winnowing Machine (Andrew Rodgers, 1737)

- Threshing Machine (Andrew Meikle, 1787)

- Reaping Machine (Cyrus McCormick, 1834)

- Steam-Powered Flour Mills

Mobile steam engines were used to drain wetlands and make land suitable for farming. Enclosure systems made more land available for farming. Advances in metalworking allowed for the mass production of stronger, sharper, and more durable farming tools. Scientists developed better fertilizers, increasing agricultural yields. These improvements made food cheaper and more accessible, leading to better nutrition and longer life expectancy, especially among children.

Labor and Working Conditions

There was a significant increase in the employment of women and children in factories and textile mills. Women and children were often paid less than men and were more adept at certain tasks due to their smaller hands. Until the 1847 law reduced working hours to 10 hours a day, workers, including children as young as eight, worked 12-hour shifts.

Workplace safety was a low priority for employers until legal regulations were introduced. Coal dust caused lung diseases among miners, and the damp conditions in textile mills had similar effects on workers. The noisy factory environment led to hearing loss, and repetitive tasks caused stress injuries. Dangerous materials like lead and mercury were commonly used, and large, heavy machinery with moving parts posed significant risks of injury or death.

Despite these conditions, governments were reluctant to impose restrictions on businesses, fearing economic damage. Workers attempted to organize and protect their rights, but employers and politicians opposed unions. Union activities were banned from 1799 to 1824. From the 1830s onwards, parliamentary acts began to provide legal protection for workers' health and safety, leading to safer working conditions. Unions like the Amalgamated Society of Engineers, founded in 1851, gained respect for their efforts to protect these rights.

Transportation and Communication Advancements

For many, the sight and sound of a train cutting through the countryside epitomized the Industrial Revolution. Initially used for short distances in mines, the first passenger train began operating between Stockton and Darlington in 1825. The first intercity passenger railway opened in 1830 between Liverpool and Manchester, using Stephenson’s Rocket locomotive. Railways revolutionized both passenger and freight transportation, drastically reducing costs and travel times.

By 1848, travelers could journey from London to Glasgow in 12 hours, a trip that previously took days by stagecoach. By 1870, Britain had over 24,000 kilometers (15,000 miles) of railway tracks. Railways connected people like never before, making travel affordable for lower-income individuals and leading to a boom in seaside tourism. Businesses could transport fresh products to distant markets, and the advertising power of new train stations across the country expanded their reach. Railways also created tens of thousands of new jobs.

Steam power also improved shipping, replacing slower sailing ships with faster, more reliable metal steamships. Shipyards became major employers. The rise of steam-powered transportation boosted the coal, iron, and steel industries. In 1786, Britain produced 70,000 tons of pig iron; by 1850, production had increased to 2.25 million tons. Sheffield became the world's leading steel producer, growing from five steel production facilities in 1170 to 135 by 1856.

Railway advancements also accelerated communication. Newspapers could be distributed nationwide in a single day, and letters and parcels were delivered within 24 hours. The development of the electric telegraph by William Fothergill Cook and Charles Wheatstone in 1837, initially for railway communication, quickly expanded to the general public and journalists, dramatically speeding up news dissemination. As the Industrial Revolution spread to other European countries and the United States, opportunities for communication and travel increased. Steamships crossing oceans and transcontinental telegraph cables connected the world more than ever before.

Social Impact

Britain's population grew from 6 million in 1750 to 21 million by 1851. The 1851 census revealed that, for the first time, more people lived in towns and cities than in rural areas. Cities like Manchester, Liverpool, Sheffield, and Halifax saw their populations grow tenfold in the 19th century. This urban concentration led to earlier marriages and higher birth rates in cities compared to rural areas.

Life in cities and towns centered around factories and coal mines became more crowded. Many families shared the same house. "In the 1840s, about 40,000 people lived in Liverpool's cellars, with an average of six people per cellar dwelling" (Armstrong, 188). Air pollution became a severe problem in many settlements. Inadequate sanitation led to the spread of diseases. Typhoid epidemics occurred in 1837, 1839, and 1847, and cholera outbreaks happened between 1831 and 1849. Urbanization also led to an increase in petty crime as anonymity in the growing cities made it easier for criminals to evade detection.

Many children worked to supplement their family's income instead of attending school. While some schools and employers provided basic education, compulsory education for children aged 5 to 12 was not implemented until the 1870s. The literacy rate in English society increased during this period, driven by the economies of scale made possible by paper production machines and the availability of affordable printed books.

Consumerism flourished as mass-produced goods created demand, resulting in more shops than ever before. Stores stocked exotic goods from all corners of the British Empire, making shopping more appealing. An urban middle class emerged, but the gap between the lowest and highest social classes widened. Factory workers had limited transferable skills and were often stuck at their current skill level. In the past, a skilled handloom weaver could save enough money over the years to start their own business with their employees. However, this method of climbing the social ladder became much more challenging. While capital became the new symbol of great wealth, replacing land, the Industrial Revolution brought a different, not necessarily better, lifestyle for most laborers.

Conclusion

The Industrial Revolution in England fundamentally transformed society. The technological, economic, and social changes of this period laid the foundations for the modern world. However, these advancements also brought significant social challenges. Worker rights, health, and safety issues, and the problems associated with rapid urbanization were the darker aspects of this era. The impact of the Industrial Revolution extended beyond England, sparking industrialization processes worldwide and leading to global transformations.