Hattusa: The Capital Founded by the Hatti Culture in 2500 BCE, Forming the Basis of the Hittite Civilization

Hattusa: The Capital of the Hittite Empire

Hattusa, the capital of the Hittite Empire, holds significant historical and archaeological value. Located 150 kilometers east of Ankara in the Boğazkale district of Çorum province, the site today offers visitors remnants of fortifications, gates, temples, and palaces, providing a comprehensive picture of the Hittite capital in the 13th century BCE.

Discovery and Excavations

Hattusa was discovered on July 28, 1834, by Charles Texier. However, the first systematic excavations at Hattusa were conducted under the guidance of Ernest Chantre in 1893-1894. During these excavations, the first cuneiform tablets from Hattusa were published. Since 1907, archaeological work has been carried out by the German Archaeological Institute.

City Structure

Hattusa was divided into two distinct areas:

- Lower City: The Old City of the Hittites, where the main temple was located.

- Upper City: A fortified palace complex surrounded by massive walls, representing the newer part of the city.

King's Gate

The King's Gate in Hattusa was an important part of the city's fortifications, adorned with a high relief statue of the War God, standing 2.25 meters tall. The original statue is now displayed in the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara. The gate was significant for both defense and ceremonial entrances.

Luwian Hieroglyphs

Many inscriptions bearing traces of the Luwian script have been found in Hattusa. These inscriptions gained importance during the late period of the Hittite Empire, especially during the reign of Suppiluliuma II. They detail the king's military successes and conquests achieved with the help of the gods.

History and Culture

- Foundation: Hattusa was first established around 2500 BCE by the Hattians, whose culture may have laid the foundation for Hittite culture.

- Settlement: During the 19th and 18th centuries BCE, the region was inhabited by Hattians and Assyrian Trade Colonies. The city, then known as Hattus, was one of the trading posts established by Assyrian colonies.

- Reconstruction: Around 1720 BCE, the city was sacked by King Anitta of Kussara, but was rebuilt a generation later by another Kussara king, becoming the capital of the Hittite Empire under the name Hattusa.

Population and Defense

At its peak, Hattusa's population was estimated to be between 40,000 and 50,000. The city covered an area of 1.8 km², surrounded by massive defensive walls stretching over 6 kilometers, equipped with watchtowers and hidden tunnels. The first sight upon entering the city is the 65-meter-long section of the reconstructed city walls. The original walls were made of mudbrick and built at intervals of 20-25 meters with defensive towers.

Tourist Visit

A complete tour of the ancient city can be done on foot or by car, following a 3-4 kilometer main circular route. The site is divided into the lower city to the north and the upper city to the south by the Kızlarkayası stream, with numerous stops along the way. It is recommended that visitors explore the city on foot to fully experience Hattusa.

Decline and Aftermath

Hattusa was destroyed around 1200 BCE along with the Hittite state, as part of the collapse of Late Bronze Age kingdoms. Excavations reveal that the city was occupied and burned after many inhabitants abandoned it in the early 12th century BCE. The area remained uninhabited until around 800 BCE, when a modest Phrygian settlement emerged.

UNESCO World Heritage List

Hattusa was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1986, ensuring its preservation and promotion. Today, Hattusa continues to be a major attraction for both domestic and international tourists.

Hattusa, with its rich historical, cultural, and archaeological heritage, is one of the most important ancient cities in Anatolia. As the capital of the Hittite Empire, it holds great significance, carrying the traces of many civilizations throughout history. Therefore, preserving Hattusa and passing it on to future generations is of utmost importance.

The Luwian hieroglyphs in Hattusa adorned a chamber symbolizing an entrance to the underworld during the final period of the Hittite Empire. This chamber was built by Suppiluliuma II, the last of the Great Kings of Hattusa (1207-1178 BCE). The hieroglyphs detail the king's conquests and successes with the help of the gods, including the conquest of Tarhuntassa.

Suppiluliuma and His Reign

Suppiluliuma, the last great king of the Hittite Empire, is characterized by efforts to consolidate and expand the empire. During his reign, the Hittites organized military campaigns to regain lost territories and strengthen the empire. Suppiluliuma II achieved significant successes in these campaigns, bringing many regions back under Hittite control.

Symbolic Entrance to the Underworld

In Hattusa, a chamber symbolizing an entrance to the underworld carries religious and ritual significance. This chamber, perhaps adorned with symbols and hieroglyphs representing the transition to the realm of the dead, signifies the sacred space where the Hittites communicated with the gods and the spirits of their ancestors. For the royal family, this chamber symbolized immortality and divine connection.

Narratives of Luwian Hieroglyphs

The Luwian hieroglyphs provide detailed information about the military campaigns and successes of Suppiluliuma II. They emphasize that the king, with the aid of the gods, conquered many countries, including Tarhuntassa. This region was crucial to the Hittite Empire, and its reconquest demonstrated the king's power and divine support. The hieroglyphs depict various scenes, including battle victories, defeated enemies, and sacrifices offered to the gods.

Cultural and Religious Significance

These hieroglyphs not only record historical events but also reflect the religious beliefs and divine connections of the Hittites. The Hittites believed they could not achieve success without the support and guidance of the gods. Therefore, the king's achievements and conquests were depicted as occurring with divine assistance. These writings reinforced the king's divine legitimacy and power.

Archaeological and Historical Value

The Luwian hieroglyphs in Hattusa are significant archaeological findings that shed light on the final period of the Hittite Empire. They provide valuable information about the reign of Suppiluliuma II and his military successes. These inscriptions are crucial for understanding the political, military, and religious structure of the Hittites.

In conclusion, the Luwian hieroglyphs in Hattusa are vital historical documents that reflect the reign of Suppiluliuma II, his military successes, and the religious beliefs of the Hittites. These writings offer valuable insights into the last great king of the Hittite Empire and form an integral part of Anatolia's rich cultural heritage.

The King's Gate in Hattusa: A Symbol of Military Power and Divine Protection

The King's Gate in Hattusa was part of the city walls of Hattusa, the capital of the Hittite Empire during the Late Bronze Age. This gate played a crucial role in the city's defense and ceremonial entrances. The most striking feature of the King's Gate is the high-relief statue of the War God, standing 2.25 meters tall. This statue symbolizes the military power of the Hittites and their devotion to war gods.

Features of the King's Gate

- Architecture and Location:

- The King's Gate is part of the eastern walls of Hattusa and is one of the city's entrance points.

- The gate is double-winged, surrounded by strong walls, and supported by defensive towers.

- War God Relief:

- The gate's most prominent feature is the high-relief statue of the War God, standing 2.25 meters tall.

- The statue depicts the war god with weapons like a shield and spear.

- The details of the statue reflect the advanced art and sculpture of the Hittites.

- Symbolic and Religious Meaning:

- The War God relief symbolizes the Hittites' devotion to the gods and the protective power of the war god.

- Such statues were used at city gates to emphasize that the gods protected the city and defended it from enemies.

Historical and Cultural Importance

The King's Gate and the War God relief are important indicators of the military and religious structure of the Hittite Empire. The Hittites believed that without the support of the gods, military success was impossible. Therefore, statues of gods at city gates and significant entrances held great importance for both defense and religious rituals.

Archaeological Excavations and Preservation of the Relief

The War God relief at the King's Gate was discovered during archaeological excavations and moved to the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara for preservation. The original relief is now displayed in this museum, showcasing the rich cultural heritage of the Hittite Empire to visitors.

Anatolian Civilizations Museum

- About the Museum: The Anatolian Civilizations Museum, located in Ankara, is one of Turkey's most important archaeological museums. It exhibits artifacts from prehistoric times to the Ottoman Empire.

- War God Relief: The War God relief from the King's Gate is displayed in the museum's Hittite section and is one of the most significant examples of Hittite art.

Reconstruction of the Hattusa City Wall: Defensive Towers Rising on Original Hittite Foundations

The 65-meter-long section of the Hattusa city wall, made of mudbrick and built with defensive towers at intervals of 20-25 meters, has been reconstructed on the original Hittite foundations. Hattusa was the capital of the Hittite Empire during the Late Bronze Age (1650 BCE).

Great Temple Area: The Sacred Center of Lower Hattusa in the Hittite Empire

The Great Temple in Lower Hattusa, the capital of the Hittite Empire during the Late Bronze Age, was built in the 14th century BCE. This temple was dedicated to the supreme deities of the Hittites, the sky and storm god Tesub, and the sun goddess Arinna.

Sphinx Gate in Hattusa: A Symbol of Strong Defense in the Hittite Empire

The Sphinx Gate, part of the city walls of Hattusa, the capital of the Hittite Empire during the Late Bronze Age, featured sphinx depictions on its four doorposts. These depictions are significant examples of Hittite art and architecture. Today, only one original sphinx remains in place, while the other two are preserved in a local museum. The Sphinx Gate was important for both defense and religious rituals, symbolizing the Hittites' connection to powerful and protective gods.

Temple District in Upper Hattusa: The Sacred Complex of the Hittite Empire

The Temple District in Upper Hattusa, the capital of the Hittite Empire during the Late Bronze Age, was one of the centers of Hittite religious and ritual life. This area contained twenty-four different sacred structures, varying in size. The temples were dedicated to various gods of the Hittite pantheon and served as important centers for religious ceremonies and rituals. The Temple District in Upper Hattusa showcases the richness of Hittite architecture and religious beliefs.

The Yerkapı Pyramid is situated on a hill and has a platform approximately 30 meters high. On this platform, there are walls and defensive towers. The main purpose of the structure was to protect the city against external threats. Underground tunnels and passages create a complex defense network within the structure. These tunnels not only allow soldiers to move quickly but also make it difficult for the enemy to breach the walls.

Underground Passage

One of the most striking features of Yerkapı is the underground passage. This passage runs under the hill and leads to a gate. Constructed with stone blocks, the passage reflects the advanced engineering knowledge of the Hittites. This passage helps maintain the defense line in the event of a siege.

The Lion Gate dates back to the 14th century BCE and was constructed during the peak of the Hittite Empire. This gate was an essential part of Hattusa's defense system and was used to control the entry and exit of the city. The location of the gate is strategically significant for the city's defense.

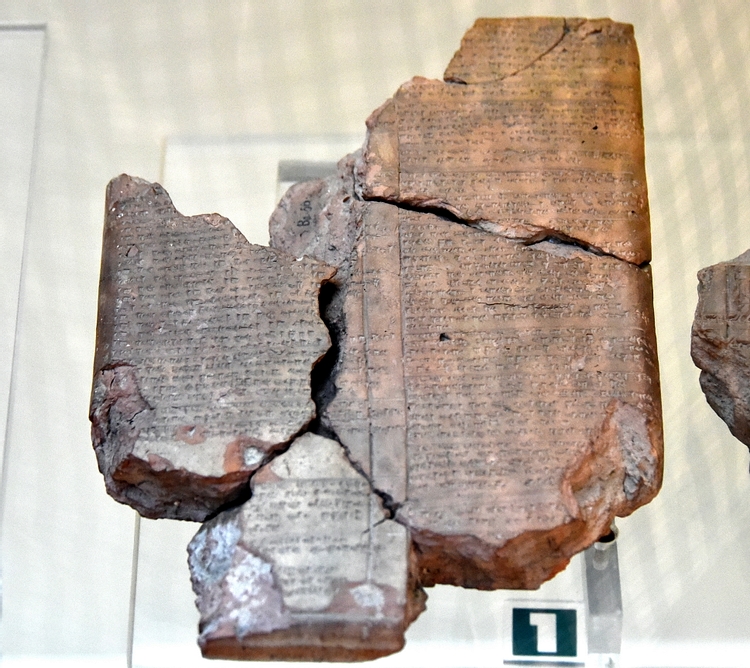

First Document Written in the Hittite Language: The Anitta Text

The text on this clay tablet is considered the first document written in the Hittite language. The tablet is a copy of the original, written during the Hittite Imperial Period. The text was authored by Anitta, son of Pithana, king of the city of Kussara. The location of Kussara is unknown today. The tablet, dating back to the 13th century BCE, but originally from the 16th century BCE, was found in Hattusa (Boğazköy) in modern-day Turkey and is now displayed in the Istanbul Archaeology Museum. The Anitta text provides valuable information about the early history and language of the Hittites.

Narrative of King Mursili II: Victories of His Father Suppiluliuma I and Relations with Egypt

Hittite king Mursili II details the wars and victories of his father, Suppiluliuma I, and mentions an important diplomatic event. After Suppiluliuma I's death, during the reign of Egyptian King Nibhururia (Tutankhamun), Queen Dahamunzu (Akhesenamun) requested a soldier from her father to marry and make the king of Egypt. This event reflects the complex diplomatic relations and marriage alliances between the Hittites and Egypt.

This information is recorded on a tablet found in Hattusa (Boğazköy) in modern-day Turkey, dating to the second half of the 14th century BCE. This significant historical document is displayed in the Istanbul Archaeology Museum and highlights the role of the Hittites in diplomacy and international relations.

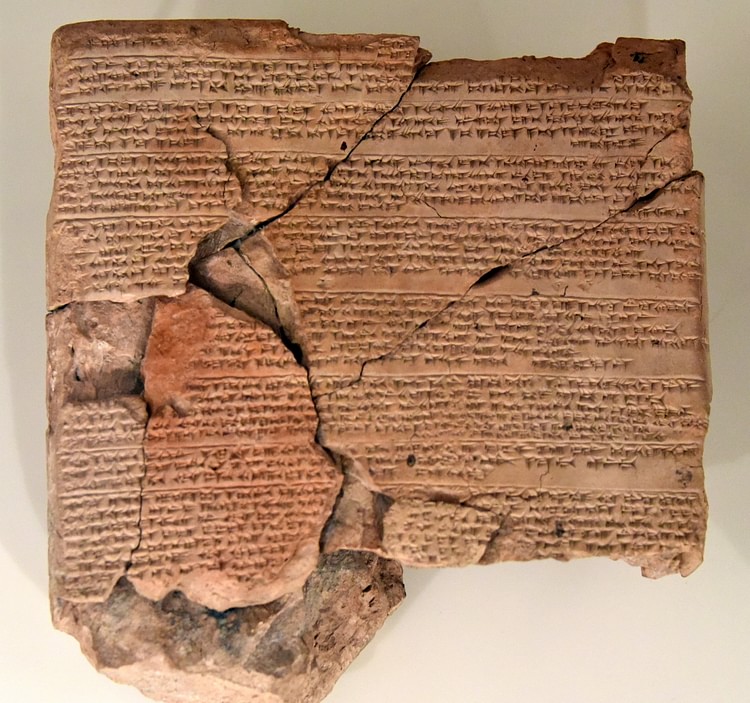

Clay Tablet Detailing Hittite Rituals: The Karahna Festivals and the God Zababa

This clay tablet details the rituals conducted by Hittite Kings at various locations in honor of various gods. The tablet specifically describes the Karahna festivals, consisting of seven ceremonies, each lasting three days. For example, the fourth festival is held on Mount Hura in honor of the god Zababa.

The tablet, dating to the 13th century BCE, comes from Hattusa (Boğazköy) in modern-day Turkey and is displayed in the Istanbul Archaeology Museum. This document provides important insights into the religious practices and devotion of the Hittites, demonstrating the complexity and care of their religious rituals and celebrations.

Clay Tablet of the Epic of Gilgamesh (VAT 12890)

This clay tablet (VAT 12890) contains a cuneiform inscription narrating a part of the Epic of Gilgamesh. The epic, written between 2150 and 1400 BCE, is dated to the 13th century BCE. The front of the tablet recounts Gilgamesh's second dream during his journey to the Cedar Forest. This passage has been partially added to the "Ishtar and the Bull of Heaven" section of the standard version of the Epic of Gilgamesh, IV. Tablet 55.

This important historical document comes from Hattusa in modern-day Turkey and is displayed in the "Cinderella, Sinbad, and Sinuhe: Arab-German Storytelling Traditions" exhibition at the Neues Museum in Berlin, Germany. The tablet highlights the different versions of the Epic of Gilgamesh and the literary culture of the Hittites, showcasing cultural interactions between ancient Mesopotamia and Anatolia.

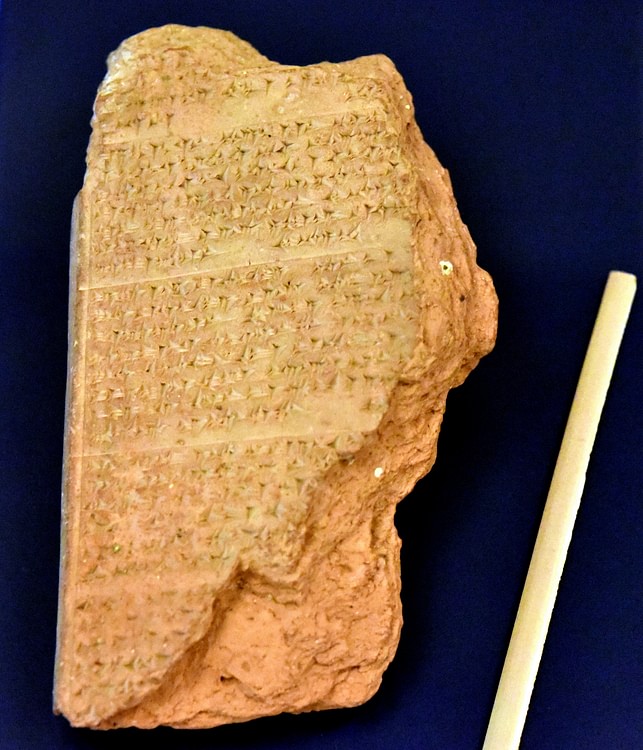

The Treaty of Kadesh: Eternal Peace between the Hittites and Egypt

This clay tablet contains the Hittite version of the "Treaty of Kadesh" (also known as the Silver Treaty or Eternal Treaty), a peace treaty between the Hittite Empire and Egypt. The treaty was made in the mid-13th century BCE between Egyptian Pharaoh Ramses II (1279-1213 BCE) and Hittite King Hattusili III (died 1237 BCE).

Significance and Content of the Treaty

The Treaty of Kadesh is one of the earliest known written peace treaties and ended the long-standing conflict between Egypt and the Hittites. The treaty contains promises from both sides to maintain peace and not attack each other. It also addresses the return of prisoners of war and the development of trade relations.

Tablets Found in the Hittite Capital of Hattusa

Three tablets of the Hittite version of the treaty were discovered in the Royal Palace archives in the Hittite capital of Hattusa. Two of these tablets are displayed in the Istanbul Archaeological Museum. The third tablet is exhibited at the Neues Museum in Berlin, Germany.

The Tablet Exhibited at the Neues Museum in Berlin

This clay tablet with cuneiform script details the treaty between Ramesses II and Hattusili III. The text of the treaty reflects the efforts of the two great powers to live in peace and the development of diplomatic relations.

Conclusion

The Treaty of Kadesh holds a significant place in history as a symbol of peace and cooperation between the Hittite and Egyptian civilizations. This treaty is a critical document for understanding the diplomatic relations and peace efforts of the ancient world. These tablets, which emerged from Hattusa in present-day Turkey, bring the diplomatic achievements of the past to the present and reveal the complex relationships of ancient civilizations to visitors.

%2FNew%20folder%20(10)%2FAA-30964613.jpg)

Travel Guide to Hattusa: Visiting, Accommodation, and Tips

Hattusa, the capital of the Hittite Empire, is an important archaeological and historical center. Located within the borders of Boğazkale district in Çorum province today, this ancient city is an indispensable destination for history enthusiasts and cultural travelers. Here are the visiting, accommodation, and other tips for tourists who want to travel to Hattusa:

How to Get to Hattusa?

Transportation

- By Road: Hattusa is approximately 150 km from Ankara. You can reach Boğazkale from Ankara via Çorum by private car or bus. There are regular minibus services from Çorum to Boğazkale.

- By Air: The nearest airport is Ankara Esenboğa Airport. You can reach Hattusa by renting a car or by taking buses through Çorum from the airport.

Visiting Information

Hattusa Ancient City

- Visiting Hours: Generally open from 8:00 AM to 5:00 PM, with variations between summer and winter seasons. It is advisable to check the visiting hours in advance.

- Entrance Fee: There is a specific entrance fee, with discounts or free entry available for Museum Card holders.

- Guided Tours: You can avail of services from professional guides in Hattusa. These guides will explain the history and significance of the ancient city in detail.

Places to Visit

- Great Temple: Dedicated to the supreme Hittite gods, the storm god Teshub and the sun goddess Arinna.

- King’s Gate: Famous for its high-relief statue of the War God.

- Sphinx Gate: Notable for its sphinx depictions.

- Yazılıkaya: The sacred open-air temple of the Hittites, known for its reliefs depicting the Twelve Gods of the Underworld.

Accommodation

Boğazkale

- Hotels and Guesthouses: Boğazkale offers various hotel and guesthouse options. These establishments provide comfortable and affordable accommodation with the advantage of being close to Hattusa.

- Hotel Aşıkoğlu: One of the closest hotels to Hattusa, known for its comfortable and clean rooms.

- Hittite Houses: A comfortable hotel decorated in traditional Hittite architecture.

- Campsites: For those who want to be in touch with nature, there are also campsites around Boğazkale.

Çorum

- Luxury Hotels: For those looking for more extensive hotel options and city amenities, accommodation in Çorum is recommended. There are 4-5 star hotels available.

- Anitta Hotel: Located in the city center and offering many modern amenities.

- Fimar Life Thermal Resort Hotel: Provides comfortable accommodation with thermal water and spa services.

Food and Drink

- Local Restaurants: In Boğazkale and Çorum, there are restaurants where you can taste local delicacies. Especially, Çorum's roasted chickpeas and regional kebabs are worth trying.

- Hitit Restaurant: Offers flavors from traditional Turkish cuisine.

- Çorum Home Cooking: Known for home-cooked meals prepared by locals.

Travel Tips

- Season: The best time to visit Hattusa is during the spring and autumn months. It can be very hot in the summer and cold in the winter.

- Clothing: It is advisable to wear comfortable walking shoes and weather-appropriate clothing. A hat and sunglasses are also important in the summer.

- Guidebook: Having a guidebook or brochures about Hattusa and the Hittites can be helpful for prior information.

- Photography: Don’t forget to bring your camera or mobile phone. The historical and natural beauty of Hattusa is worth photographing.

Hattusa is a captivating destination for history enthusiasts, offering the opportunity to explore an important center of the ancient world. With this guide, you will have the necessary information to plan your trip and discover the rich history of Hattusa.